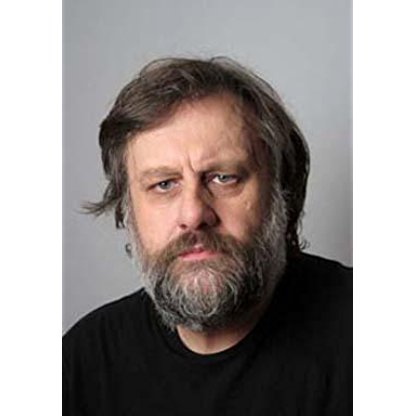

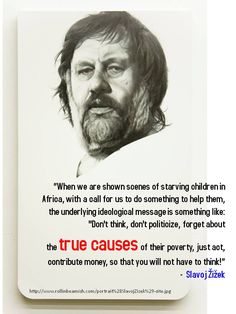

| Who is it? | Writer |

| Birth Day | March 21, 1949 |

| Slavoj Zizek age | 74 YEARS OLD |

| Birth Sign | Aries |

| Alma mater | University of Ljubljana University of Paris VIII |

| Era | 20th-/21st-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Ljubljana school of psychoanalysis Lacanian psychoanalysis Hegelianism Freudo-Marxism |

| Institutions | University of Ljubljana New York University Birkbeck, University of London |

| Main interests | Ideology Marxism ontology political theory psychoanalysis cultural studies film theory theology German idealism dialectic |

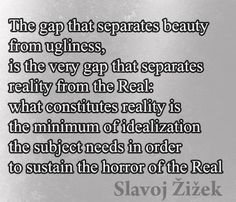

| Notable ideas | Ideology as an unconscious fantasy that structures reality; revival of dialectical materialism |

Slavoj Zizek, a renowned writer, is estimated to have a net worth ranging from $100,000 to $1 million in 2024. Born in 1949, Zizek has established himself as a prominent philosopher, cultural critic, and psychoanalytic theorist. Known for his unique and provocative insights, Zizek's works have gained substantial recognition worldwide. As an influential author, lecturer, and political commentator, his net worth reflects the success and impact of his literary contributions and intellectual career.

All hearts were beating for you as long as you were perceived as just another version of the liberal-democratic protest against the authoritarian state. The moment it became clear that you rejected global capitalism, reporting on Pussy Riot became much more ambiguous.

Žižek was born in Ljubljana, SR Slovenia, Yugoslavia, into a middle-class family. His father Jože Žižek was an Economist and civil servant from the region of Prekmurje in eastern Slovenia. His mother Vesna, native of the Gorizia Hills in the Slovenian Littoral, was an accountant in a state enterprise. His parents were atheists. He spent most of his childhood in the coastal town of Portorož, where he was exposed to Western film, theory and popular culture. When Slavoj was a teenager his family moved back to Ljubljana where he attended Bežigrad High School. In the 1960s and early 1970s, Slavoj was exposed to a lot of western philosophy in Zagreb.

He had already begun reading French structuralists prior to entering university, and in 1967 he published the first translation of a text by Jacques Derrida into Slovenian. An early influence at university, Božidar Debenjak, taught the philosophy of German idealism and introduced the thought of the Frankfurt School to Slovenia. Debenjak's reading of Marx's Das Kapital from the perspective of Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit influenced many Future Slovenian Philosophers, including Žižek.

Žižek frequented the circles of dissident intellectuals, including the Heideggerian Philosophers Tine Hribar and Ivo Urbančič, and published articles in alternative magazines, such as Praxis, Tribuna and Problemi, which he also edited. In 1971 he accepted a job as an assistant researcher with the promise of tenure, but was dismissed after his Master's thesis was accused of being "non-Marxist". He graduated from the University of Ljubljana in 1981 with a Doctor of Arts in Philosophy for his dissertation entitled The Theoretical and Practical Relevance of French Structuralism.

In the late 1980s, Žižek came to public attention as a columnist for the alternative youth magazine Mladina, which was critical of Tito's policies, Yugoslav politics, especially the militarization of society. He was a member of the Communist Party of Slovenia until October 1988, when he quit in protest against the JBTZ trial together with 32 other Slovenian intellectuals. Between 1988 and 1990, he was actively involved in several political and civil society movements which fought for the democratization of Slovenia, most notably the Committee for the Defence of Human Rights. In the first free elections in 1990, he ran as the Liberal Democratic Party's candidate for Slovenian presidency (an office formally abolished in the 1991 constitution).

In 1985, Žižek completed a second doctorate (Doctor of Philosophy in psychoanalysis) at the University of Paris VIII under Jacques-Alain Miller and François Regnault.

He wrote the introduction to Slovene translations of G. K. Chesterton's and John Le Carré's detective novels. In 1988, he published his first book dedicated entirely to film theory. He achieved international recognition as a social theorist with the 1989 publication of his first book in English, The Sublime Object of Ideology.

In 1989, Žižek published his first English text, The Sublime Object of Ideology, in which he departed from traditional Marxist theory to develop a materialist conception of ideology that drew heavily on Lacanian psychoanalysis and Hegelian idealism. His early theoretical work became increasingly eclectic and political in the 1990s, dealing frequently in the critical analysis of disparate forms of popular culture and making him a popular figure of the academic left. A critic of capitalism, neoliberalism and political correctness, Žižek calls himself a political radical, and his work has been characterized as challenging orthodoxies of both the political right and the social-liberal universities.

Žižek and his thought have been the subject of several documentaries. The 1996 Liebe Dein Symptom wie Dich selbst! is a German documentary on him. In the 2004 The Reality of the Virtual, Žižek gave a one-hour lecture on his interpretation of Lacan's tripartite thesis of the imaginary, the symbolic, and the real. Zizek! is a 2005 documentary by Astra Taylor on his philosophy. The 2006 The Pervert's Guide to Cinema and 2012 The Pervert's Guide to Ideology also portray Žižek's ideas and cultural criticism. Examined Life (2008) features Žižek speaking about his conception of ecology at a garbage dump. He was also featured in the 2011 Marx Reloaded, directed by Jason Barker.

In 2003, Žižek wrote text to accompany Bruce Weber's photographs in a catalog for Abercrombie & Fitch. Questioned as to the seemliness of a major intellectual writing ad copy, Žižek told The Boston Globe, "If I were asked to choose between doing things like this to earn money and becoming fully employed as an American academic, kissing ass to get a tenured post, I would with pleasure choose writing for such journals!"

His body of writing spans dense theoretical polemics, academic tomes, and accessible introductory books; in addition, he has taken part in various film projects, including two documentary collaborations with Director Sophie Fiennes, The Pervert's Guide to Cinema (2006) and The Pervert's Guide to Ideology (2012). His work has impacted both academic and widespread public audiences (see for Example his commentary in the 2003 Abercrombie and Fitch Quarterly).

Hundreds of academics have addressed aspects of Žižek's work in professional papers, and in 2007, the International Journal of Žižek Studies was established for the discussion of his work.

In a 2008 interview with Amy Goodman on Democracy Now!, he described himself as a "communist in a qualified sense," and in another appearance in October 2009 he described himself as a "radical leftist." The following year Žižek appeared in the Arte documentary Marx Reloaded in which he defended the idea of communism.

Foreign Policy named Žižek one of its 2012 Top 100 Global Thinkers "for giving voice to an era of absurdity."

In January 2013, the British Royal Opera House announced that four new operas inspired by Žižek's writings have been commissioned.

On 11 July 2014, American weekly newsmagazine Newsweek reported that in an article published in 2006 Žižek plagiarized substantial passages from an earlier review that first appeared in the journal American Renaissance, a publication condemned by the Southern Poverty Law Center as the organ of a "white nationalist hate group." However, in response to the allegations, Žižek stated:

In 2016, during a conversation with Gary Younge at a Guardian Live event, Žižek endorsed Donald Trump for the US presidency. He described Trump as a paradox, basically a centrist liberal in most of his positions, desperately trying to mask this by dirty jokes and stupidities. In an opinion piece, published e.g. in Die Zeit, he described Hillary Clinton as the much less suitable alternative. Some comments referred to Žižek not being too different to Trump – both thriving on their quotability, provoking outrage and both being, in their own very different ways, "big personalities" in the media with Slovenian spouses. In an interview with the BBC, Žižek did however state that he thought Trump was "horrible" and his support would have been based on an attempt to encourage the Democratic Party to return to more centrist ideas and adopt more leftist ideas too.

Žižek's refusal to present an alternative vision has led critics to accuse him of using unsustainable Marxist categories of analysis and having a 19th-century understanding of class. For Example, Ernesto Laclau argued that "Žižek uses class as a sort of deus ex machina to play the role of the good guy against the multicultural devils." The use of such analysis, however, is not systematic and draws on critical accounts of Stalinism and Maoism, as well as post-structuralism and Lacanian psychoanalysis.

In a very negative review of Žižek's magnum opus Less than Nothing, the British political Philosopher John Gray attacked Žižek for his celebrations of violence, his failure to ground his theories in historical facts, and his ‘formless radicalism’ which, according to Gray, professes to be communist yet lacks the conviction that communism could ever be successfully realized. Gray concluded that Žižek's work, though entertaining, is intellectually worthless: 'Achieving a deceptive substance by endlessly reiterating an essentially empty vision, Žižek's work amounts in the end to less than nothing.'