| Who is it? | Human Rights Activist |

| Birth Day | June 21, 1947 |

| Birth Place | Hamadan, Iranian |

| Shirin Ebadi age | 76 YEARS OLD |

| Birth Sign | Cancer |

| Residence | London, England |

| Alma mater | University of Tehran |

| Occupation | Lawyer Judge |

| Known for | Defenders of Human Rights Center |

| Awards | Rafto Prize (2001) Nobel Peace Prize (2003) JPM Interfaith Award (2004) Legion of Honour (2006) |

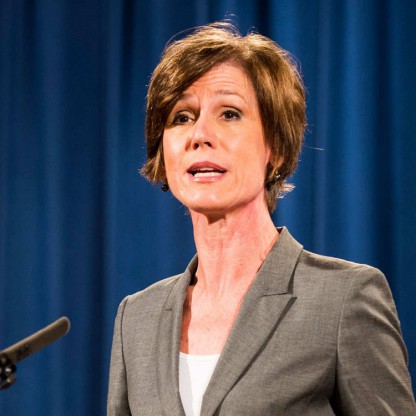

Shirin Ebadi is a prominent Iranian human rights activist, best known for her unwavering commitment to advocating for justice and equality. Despite facing numerous challenges and obstacles throughout her career, her accomplishments have not gone unnoticed. As of 2024, Shirin Ebadi's net worth is estimated to be around $4 million. Her relentless efforts in defending the rights of marginalized individuals and her notable achievements, such as becoming the first Iranian woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize in 2003, have undoubtedly contributed to her financial success. Shirin Ebadi's dedication and passion for championing human rights continue to inspire countless individuals worldwide.

In the last 23 years, from the day I was stripped of my judgeship to the years of doing battle in the revolutionary courts of Tehran, I had repeated one refrain: an interpretation of Islam that is in harmony with equality and democracy is an authentic expression of faith. It is not religion that binds women, but the selective dictates of those who wish them cloistered. That belief, along with the conviction that change in Iran must come peacefully and from within, has underpinned my work."

Ebadi was born in Hamadan, Iran. Her Father, Mohammad Ali Ebadi, was the city's chief notary public and a professor of commercial law. Her family moved to Tehran in 1948.

At the same time, Ebadi expresses a nationalist love of Iran and a critical view of the Western world. She opposed the pro-Western Shah, initially supported the Islamic Revolution, and remembers the CIA's 1953 overthrow of prime minister Mohammad Mosaddeq with rage.

She was admitted to the law department of the University of Tehran in 1965 and in 1969, upon graduation, passed the qualification exams to become a judge. After a six-month internship period, she officially became a judge in March 1969. She continued her studies in University of Tehran in the meantime to pursue a doctorate's degree in law in 1971. In 1975, she became the first woman President of the Tehran city court and served until the 1979 Iranian revolution. She was also the first ever woman judge in Iran.

Ebadi was demoted to a secretarial position at Tehran city court from her position as President under the insistence from conservative clerics after the 1979 Revolution. Clerics had insisted that Islam prohibits women from becoming judges. She and other female judges protested and were assigned to the slightly higher position of "law expert." She eventually requested early retirement as the situation remained unchanged.

Ebadi also represented the family of Ezzat Ebrahim-Nejad, who was killed in the Iranian student protests in July 1999. In 2000 Ebadi was accused of manipulating the videotaped confession of Amir Farshad Ebrahimi, a former member of the Ansar-e Hezbollah. Ebrahimi confessed his involvement in attacks made by the organization on the orders of high-level conservative authorities, which have included the killing of Ezzat Ebrahim-Nejad and attacks against members of President Khatami's cabinet. Ebadi claimed that she had only videotaped Amir Farshad Ebrahimi's confessions in order to present them to the court. This case was named "Tape makers" by hardliners who questioned the credibility of his videotaped deposition as well as his motives. Ebadi and Rohami were sentenced to five years in jail and suspension of their law licenses for sending Ebrahimi's videotaped deposition to Islamic President Khatami and the head of the Islamic judiciary. The sentences were later vacated by the Islamic judiciary's supreme court, but they did not forgive Ebarahimi's videotaped confession and sentenced him to 48 months jail, including 16 months in solitary confinement. This case brought increased focus on Iran from human rights groups abroad.

She also helped in the drafting of the original text of a law against physical abuse of children, which was passed by the Iranian parliament in 2002. Female members of Parliament also asked Ebadi to draft a law explaining how a woman's right to divorce her husband is in line with Sharia (Islamic Law). Ebadi presented the bill before the government, but the male members made her leave without considering the bill, according to Ebadi's memoir.

On 10 October 2003, Shirin Ebadi was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for her efforts for democracy and human rights, especially for the rights of women and children. The selection committee praised her as a "courageous person" who "has never heeded the threat to her own safety". Now she travels abroad lecturing in the West. She is against a policy of forced regime change. Her husband, Javad Tavassolian, was an advisor to President Khatami.

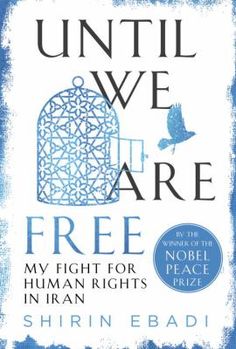

In 2004, Ebadi filed a lawsuit against the U.S. Department of Treasury because of restrictions she faced over publishing her memoir in the United States. American trade laws include prohibitions on Writers from embargoed countries. The law also banned American literary agent Wendy Strothman from working with Ebadi. Azar Nafisi wrote a letter in support of Ebadi. Nafisi said that the law infringes on the First Amendment. After a long legal battle, Ebadi won and was able to publish her memoir in the United States.

According to the Associated Press, on 27 August 2007, Ebadi was sued by a Canadian author and political analyst, Shahir Shahidsaless—who writes and publishes in Persian—in U.S. District Court in Manhattan saying she reneged on getting a publisher for a book she had requested him to write under her supervision, titled A Useful Enemy. The initial suit was dismissed due to lack of jurisdiction of the court, and not the substance of the case, which was never tried. The case is currently being considered at the New York State Court.

In December 2008, Iranian police shut down the office of a human rights group led by her. Another human rights group, Human Rights Watch, has said it was "extremely worried" about Ebadi's safety.

Ebadi said while in London in late November 2009 that her Nobel Peace Prize medal and diploma had been taken from their bank box alongside her Légion d'honneur and a ring she had received from Germany's association of journalists. She said they had been taken by the Revolutionary Court approximately three weeks previously. Ebadi also said her bank account was frozen by authorities. Norwegian Minister of Foreign Affairs Jonas Gahr Støre expressed his "shock and disbelief" at the incident. The Iranian foreign ministry subsequently denied the confiscation, and also criticized Norway for interfering in Iran's affairs.

However, in a 2012 interview, Ebadi has stated: "The [Iranian] people want to stop enrichment but the government doesn't Listen. Iran is situated on a fault line and people are scared of a Fukushima type of situation happening. We want peace, security, and economic welfare, and we cannot forgo all of our other rights for nuclear Energy. The government claims it is not making a bomb. But I am not a member of the government, so I cannot speak to this directly. The fear is that if they do, Israel will be wiped out. If the Iranian people are able to topple the government, this could improve the situation. [In 2009] the people of Iran rose up and were badly suppressed. Right now, Iran is the country with the most journalists in prison. This is the price people are paying."

Since the victory of Hassan Rouhani in the 2013 Iranian presidential election, Shirin Ebadi in various occasions has expressed her worry about the growing human rights violations in her homeland. Ebadi in her Dec. 2013 speech at Human Rights Day seminar at Leiden University angrily said: "I will shut up but the problems of Iran will not be solved".

In Iran, officials of the Islamic Republic were either silent or critical of the selection of Ebadi, calling it a political act by a pro-Western institution and were also critical when Ebadi did not cover her hair at the Nobel award ceremony. IRNA reported it in few lines that the evening newspapers and the Iranian state media waited hours to report the Nobel committee's decision—and then only as the last item on the radio news update. Reformist officials are said to have "generally welcomed the award", but "come under attack for doing so." Reformist President Mohammad Khatami did not officially congratulate Ms. Ebadi and stated that although the scientific Nobels are important, the Peace Prize is "not very important" and was awarded to Ebadi on the basis of "totally political criteria". Vice President Mohammad Ali Abtahi, the only official to initially congratulate Ebadi, defended the President saying "abusing the President's words about Ms. Ebadi is tantamount to abusing the prize bestowed on her for political considerations".

In light of the increased power of ISIL, Ebadi communicated in April 2015 that she believes the Western world should spend money funding education and an end to corruption rather than fighting with guns and bombs. She reasons that because the Islamic State stems from an ideology based on a "wrong interpretation of Islam," physical force will not end ISIS because it will not end its beliefs.

In 2018, in an interview with Bloomberg, Ebadi stated her belief that the Islamic Republic has reached a point of which it is now un-reformable. Ebadi called for a referendum on the Islamic Republic.

Ebadi has also defended various child abuse cases, including the case of Arian Golshani, a child who was abused for years and then beaten to death by her Father and stepbrother. This case gained international attention and caused controversy in Iran. Ebadi used this case to highlight Iran’s problematic child custody laws, whereby custody of children in divorce is usually given to the Father, even in the case of Arian, where her mother had told the court that the Father was abusive and had begged for custody of her daughter. Ebadi also handled the case of Leila, a teenage girl who was gang-raped and murdered. Leila’s family became homeless trying to cover the costs of the execution of the perpetrators owed to the government, because in the Islamic Republic of Iran, it is the victim's family's responsibility to pay to restore their honor when a girl is raped by paying the government to execute the perpetrator. Ebadi was not able to achieve a victory in this case, but she brought international attention to this problematic law. Ebadi also handled a few cases dealing with bans of periodicals (including the cases of Habibollah Peyman, Abbas Marufi, and Faraj Sarkouhi). She has also established two non-governmental organizations in Iran with western funding, the Society for Protecting the Rights of the Child (SPRC) (1994) and the Defenders of Human Rights Center (DHRC) in 2001.