| Who is it? | Actress |

| Birth Place | Chinese |

| Chinese | 大明 |

| TranscriptionsStandard MandarinHanyu PinyinWade–GilesIPAWuSuzhouneseYue: CantoneseYale RomanizationIPAJyutpingSouthern MinTâi-lô | Transcriptions Standard Mandarin Hanyu Pinyin Míng cháo Wade–Giles Ming ch'ao IPA [mǐŋ ʈʂʰǎu] Wu Suzhounese Mín záu Yue: Cantonese Yale Romanization Ming chiu IPA [mȅŋ tsʰȉːu] Jyutping Ming ciu Southern Min Tâi-lô Bîng tiâu Míng cháoMing ch'ao[mǐŋ ʈʂʰǎu]Mín záuMing chiu[mȅŋ tsʰȉːu]Ming ciuBîng tiâu |

| Hanyu Pinyin | Dà Míng Dì Guó |

| Wade–Giles | Ta Ming Ti Kuo |

| IPA | [tàːi mȅŋ tɐ̄i kʷɔ̄ːk̚] |

| Suzhounese | Mín záu |

| Yale Romanization | Daai Ming Dai Gwok |

| Jyutping | daai ming dai gwok |

| Tâi-lô | Bîng tiâu |

| TranscriptionsStandard MandarinHanyu PinyinYue: CantoneseYale RomanizationIPA | Transcriptions Standard Mandarin Hanyu Pinyin Dà Míng Yue: Cantonese Yale Romanization Daai Ming IPA [tàːi mȅŋ] Dà MíngDaai Ming[tàːi mȅŋ] |

| Traditional Chinese | 大明帝國 |

| Simplified Chinese | 大明帝国 |

| TranscriptionsStandard MandarinHanyu PinyinWade–GilesWuRomanizationYue: CantoneseYale RomanizationIPAJyutping | Transcriptions Standard Mandarin Hanyu Pinyin Dà Míng Dì Guó Wade–Giles Ta Ming Ti Kuo Wu Romanization da men di kueh/koh Yue: Cantonese Yale Romanization Daai Ming Dai Gwok IPA [tàːi mȅŋ tɐ̄i kʷɔ̄ːk̚] Jyutping daai ming dai gwok Dà Míng Dì GuóTa Ming Ti Kuoda men di kueh/kohDaai Ming Dai Gwok[tàːi mȅŋ tɐ̄i kʷɔ̄ːk̚]daai ming dai gwok |

| Romanization | da men di kueh/koh |

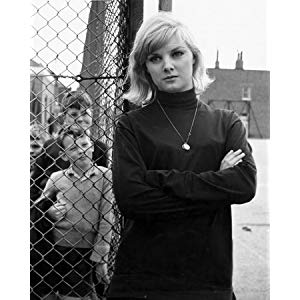

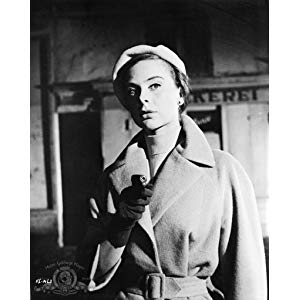

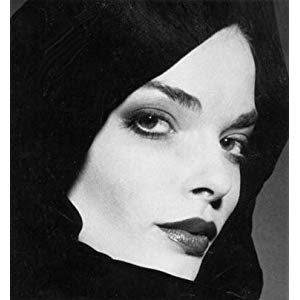

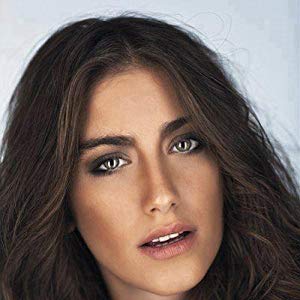

Ming Zhao, widely recognized as a talented actress in the Chinese entertainment industry, is projected to have a net worth of $20 million by 2024. With her charismatic on-screen presence and remarkable acting skills, Ming Zhao has captivated audiences and garnered a significant following. Through the years, she has dazzled viewers with her versatile performances in various dramas and movies, solidifying her status as one of China's most sought-after actresses. With her immense success and growing popularity, it comes as no surprise that her net worth continues to skyrocket, reflecting her undeniable talent and hard work in the world of acting.

Sinologist historians debate the population figures for each era in the Ming dynasty. The Historian Timothy Brook notes that the Ming government census figures are dubious since fiscal obligations prompted many families to underreport the number of people in their households and many county officials to underreport the number of households in their jurisdiction. Children were often underreported, especially female children, as shown by skewed population statistics throughout the Ming. Even adult women were underreported; for Example, the Daming Prefecture in North Zhili reported a population of 378,167 males and 226,982 females in 1502. The government attempted to revise the census figures using estimates of the expected average number of people in each household, but this did not solve the widespread Problem of tax registration. Some part of the gender imbalance may be attributed to the practice of female infanticide. The practice is well documented in China, going back over two thousand years, and it was described as "rampant" and "practiced by almost every family" by contemporary authors. However, the dramatically skewed sex ratios, which many counties reported exceeding 2:1 by 1586, cannot likely be explained by infanticide alone.

During the last years of the Wanli era and those of his two successors, an economic crisis developed that was centered on a sudden widespread lack of the empire's chief medium of exchange: silver. The Portuguese first established trade with China in 1516, trading Japanese silver for Chinese silk, and after some initial hostilities gained consent from the Ming court in 1557 to settle Macau as their permanent trade base in China. Their role in providing silver was gradually surpassed by the Spanish, while even the Dutch challenged them for control of this trade. Philip IV of Spain (reigned 1621–1665) began cracking down on illegal smuggling of silver from New Spain and Peru across the Pacific through the Philippines towards China, in favor of shipping American-mined silver through Spanish ports. In 1639 the new Tokugawa regime of Japan shut down most of its foreign trade with European powers, cutting off another source of silver coming into China. These events occurring at roughly the same time caused a dramatic spike in the value of silver and made paying taxes nearly impossible for most provinces. People began hoarding precious silver as there was progressively less of it, forcing the ratio of the value of copper to silver into a steep decline. In the 1630s a string of one thousand copper coins equaled an ounce of silver; by 1640 that sum could fetch half an ounce; and, by 1643 only one-third of an ounce. For peasants this meant economic disaster, since they paid taxes in silver while conducting local trade and crop sales in copper.

Li Shizhen (1518–93) – one of the most renowned pharmacologists and Physicians in Chinese history – belonged to the late Ming period. His Bencao Gangmu is a medical text with 1,892 entries, each entry with its own name called a gang. The mu in the title refers to the synonyms of each name. Inoculation, although it can be traced to earlier Chinese folk Medicine, was detailed in Chinese texts by the sixteenth century. Throughout the Ming dynasty, around fifty texts were published on the treatment of smallpox. In regards to oral hygiene, the ancient Egyptians had a primitive toothbrush of a twig frayed at the end, but the Chinese were the first to invent the modern bristle toothbrush in 1498, although it used stiff pig hair.

Modern scholars debate whether the Ming dynasty had sovereignty over Tibet. Some believe it was a relationship of loose suzerainty that was largely cut off when the Jiajing Emperor (r. 1521–67) persecuted Buddhism in favor of Daoism at court. Others argue that the significant religious nature of the relationship with Tibetan lamas is underrepresented in modern scholarship. Others note the Ming need for Central Asian horses and the need to maintain the tea-horse trade.

Focusing on agriculture in his Nongzheng Quanshu, the agronomist Xu Guangqi (1562–1633) took an interest in irrigation, fertilizers, famine relief, economic and textile crops, and empirical observation of the elements that gave insight into early understandings of chemistry.

In contrast to Xu Xiake, who focused on technical aspects in his travel literature, the Chinese poet and official Yuan Hongdao (1568–1610) used travel literature to express his desires for individualism as well as autonomy from and frustration with Confucian court politics. Yuan desired to free himself from the ethical compromises that were inseparable from the career of a scholar-official. This anti-official sentiment in Yuan's travel literature and poetry was actually following in the tradition of the Song dynasty poet and official Su Shi (1037–1101). Yuan Hongdao and his two brothers, Yuan Zongdao (1560–1600) and Yuan Zhongdao (1570–1623), were the founders of the Gong'an School of letters. This highly individualistic school of poetry and prose was criticized by the Confucian establishment for its association with intense sensual lyricism, which was also apparent in Ming vernacular novels such as the Jin Ping Mei. Yet even gentry and scholar-officials were affected by the new popular romantic literature, seeking courtesans as soulmates to reenact the heroic love stories that arranged marriages often could not provide or accommodate.

The Ming sporadically sent armed forays into Tibet during the 14th century, which the Tibetans successfully resisted. Several scholars point out that unlike the preceding Mongols, the Ming dynasty did not garrison permanent troops in Tibet. The Wanli Emperor (r. 1572–1620) attempted to reestablish Sino-Tibetan relations in the wake of a Mongol-Tibetan alliance initiated in 1578, an alliance which affected the foreign policy of the subsequent Manchu Qing dynasty (1644–1912) in their support for the Dalai Lama of the Yellow Hat sect. By the late 16th century, the Mongols proved to be successful armed protectors of the Yellow Hat Dalai Lama after their increasing presence in the Amdo region, culminating in the conquest of Tibet by Güshi Khan (1582–1655) in 1642, establishing the Khoshut Khanate.

The Chinese were intrigued with European Technology, but so were visiting Europeans of Chinese Technology. In 1584, Abraham Ortelius (1527–1598) featured in his atlas Theatrum Orbis Terrarum the peculiar Chinese innovation of mounting masts and sails onto carriages, just like Chinese ships. Gonzales de Mendoza also mentioned this a year later – noting even the designs of them on Chinese silken robes – while Gerardus Mercator (1512–94) featured them in his atlas, John Milton (1608–74) in one of his famous poems, and Andreas Everardus van Braam Houckgeest (1739–801) in the writings of his travel diary in China. The encyclopedist Song Yingxing (1587–1666) documented a wide array of technologies, metallurgic and industrial processes in his Tiangong Kaiwu encyclopedia of 1637. This includes mechanical and hydraulic powered devices for agriculture and irrigation, nautical Technology such as vessel types and snorkeling gear for pearl divers, the annual processes of sericulture and weaving with the loom, metallurgic processes such as the crucible technique and quenching, Manufacturing processes such as for roasting iron pyrite in converting sulphide to oxide in sulfur used in gunpowder compositions – illustrating how ore was piled up with coal briquettes in an earthen furnace with a still-head that sent over sulfur as vapor that would solidify and crystallize – and the use of gunpowder weapons such as a naval mine ignited by use of a rip-cord and steel flint wheel.

Informal essay and travel writing was another highlight. Xu Xiake (1587–1641), a travel literature author, published his Travel Diaries in 404,000 written characters, with information on everything from local geography to mineralogy. The first reference to the publishing of private newspapers in Beijing was in 1582; by 1638 the Beijing Gazette switched from using woodblock print to movable type printing. The new literary field of the moral guide to Business ethics was developed during the late Ming period, for the readership of the merchant class.

The Hongwu Emperor forbade eunuchs to learn how to read or engage in politics. Whether or not these restrictions were carried out with absolute success in his reign, eunuchs during the Yongle Emperor's reign and afterwards managed huge imperial workshops, commanded armies, and participated in matters of appointment and promotion of officials. The eunuchs developed their own bureaucracy that was organized parallel to but was not subject to the civil Service bureaucracy. Although there were several dictatorial eunuchs throughout the Ming, such as Wang Zhen, Wang Zhi, and Liu Jin, excessive tyrannical eunuch power did not become evident until the 1590s when the Wanli Emperor increased their rights over the civil bureaucracy and granted them power to collect provincial taxes.

The liberal views of Wang Yangming were opposed by the Censorate and by the Donglin Academy, re-established in 1604. These conservatives wanted a revival of orthodox Confucian ethics. Conservatives such as Gu Xiancheng (1550–1612) argued against Wang's idea of innate moral knowledge, stating that this was simply a legitimization for unscrupulous behavior such as greedy pursuits and personal gain. These two strands of Confucian thought, hardened by Chinese scholars' notions of obligation towards their mentors, developed into pervasive factionalism among the ministers of state, who used any opportunity to impeach members of the other faction from court.

Seizing opportunity, the Eight Banners crossed the Great Wall after the Ming border general Wu Sangui (1612–1678) opened the gates at Shanhai Pass. This occurred shortly after he learned about the fate of the capital and an army of Li Zicheng marching towards him; weighing his options of alliance, he decided to side with the Manchus. The Eight Banners under the Manchu Prince Dorgon (1612–50) and Wu Sangui approached Beijing after the army sent by Li was destroyed at Shanhaiguan; the Prince of Shun's army fled the capital on the fourth of June. On 6 June, the Manchus and Wu entered the capital and proclaimed the young Shunzhi Emperor ruler of China. After being forced out of Xi'an by the Qing, chased along the Han River to Wuchang, and finally along the northern border of Jiangxi province, Li Zicheng died there in the summer of 1645, thus ending the Shun dynasty. One report says his death was a suicide; another states that he was beaten to death by peasants after he was caught stealing their food.

A Jurchen tribal leader named Nurhaci (r. 1616–26), starting with just a small tribe, rapidly gained control over all the Manchurian tribes. During the Japanese invasions of Joseon Korea in the 1590s, he offered to lead his tribes in support of the Ming and Joseon army. This offer was declined, but he was granted honorific Ming titles for his gesture. Recognizing the weakness of Ming authority north of their border, he united all of the adjacent northern tribes and consolidated power in the region surrounding his homeland as the Jurchen Jin dynasty had done previously. In 1610, he broke relations with the Ming court, and in 1618 demanded a tribute from them to redress "Seven Grievances".

Compared to the flourishing of science and Technology in the Song dynasty, the Ming dynasty perhaps saw fewer advancements in science and Technology compared to the pace of discovery in the Western world. In fact, key advances in Chinese science in the late Ming were spurred by contact with Europe. In 1626 Johann Adam Schall von Bell wrote the first Chinese treatise on the telescope, the Yuanjingshuo (Far Seeing Optic Glass); in 1634 the Chongzhen Emperor acquired the telescope of the late Johann Schreck (1576–1630). The heliocentric model of the solar system was rejected by the Catholic missionaries in China, but Johannes Kepler and Galileo Galilei's ideas slowly trickled into China starting with the Polish Jesuit Michael Boym (1612–59) in 1627, Adam Schall von Bell's treatise in 1640, and finally Joseph Edkins, Alex Wylie, and John Fryer in the 19th century. Catholic Jesuits in China would promote Copernican theory at court, yet at the same time embrace the Ptolemaic system in their writing; it was not until 1865 that Catholic missionaries in China sponsored the heliocentric model as their Protestant peers did. Although Shen Kuo (1031–95) and Guo Shoujing (1231–1316) had laid the basis for trigonometry in China, another important work in Chinese trigonometry would not be published again until 1607 with the efforts of Xu Guangqi and Matteo Ricci. Ironically, some inventions which had their origins in ancient China were reintroduced to China from Europe during the late Ming; for Example, the field mill.

A peasant soldier named Li Zicheng mutinied with his fellow Soldiers in western Shaanxi in the early 1630s after the Ming government failed to ship much-needed supplies there. In 1634 he was captured by a Ming general and released only on the terms that he return to Service. The agreement soon broke down when a local magistrate had thirty-six of his fellow rebels executed; Li's troops retaliated by killing the officials and continued to lead a rebellion based in Rongyang, central Henan province by 1635. By the 1640s, an ex-soldier and rival to Li – Zhang Xianzhong (1606–47) – had created a firm rebel base in Chengdu, Sichuan, while Li's center of power was in Hubei with extended influence over Shaanxi and Henan.

By 1636, Nurhaci's son Huang Taiji renamed his dynasty from the "Later Jin" to the "Great Qing" at Mukden, which had fallen to Qing forces in 1621 and was made their capital in 1625. Huang Taiji also adopted the Chinese imperial title huangdi, declared the Chongde ("Revering Virtue") era, and changed the ethnic name of his people from "Jurchen" to "Manchu". In 1638 the Manchu defeated and conquered Ming China's traditional ally Joseon with an army of 100,000 troops in the Second Manchu invasion of Korea. Shortly after, the Koreans renounced their long-held loyalty to the Ming dynasty.

Connoisseurship in the late Ming period centered on these items of refined artistic taste, which provided work for art dealers and even underground scammers who themselves made imitations and false attributions. The Jesuit Matteo Ricci while staying in Nanjing wrote that Chinese scam artists were ingenious at making forgeries and huge profits. However, there were guides to help the wary new connoisseur; Liu Tong (died 1637) wrote a book printed in 1635 that told his readers how to spot fake and authentic pieces of art. He revealed that a Xuande era (1426–1435) bronzework could be authenticated by judging its sheen; porcelain wares from the Yongle era (1402–1424) could be judged authentic by their thickness.

During his mission, Ricci was also contacted in Beijing by one of the approximately 5,000 Kaifeng Jews and introduced them and their long history in China to Europe. However, the 1642 flood caused by Kaifeng's Ming governor devastated the community, which lost five of its twelve families, its synagogue, and most of its Torah.

Despite the loss of Beijing and the death of the Emperor, the Ming were not yet totally destroyed. Nanjing, Fujian, Guangdong, Shanxi, and Yunnan were all strongholds of Ming resistance. However, there were several pretenders for the Ming throne, and their forces were divided. These scattered Ming remnants in southern China after 1644 were collectively designated by 19th-century historians as the Southern Ming. Each bastion of resistance was individually defeated by the Qing until 1662, when the last southern Ming Emperor died, the Yongli Emperor, Zhu Youlang. The last Ming Princes to hold out were the Prince of Ningjing Zhu Shugui and the son of Zhu Yihai, the Prince of Lu Zhu Honghuan (朱弘桓) who stayed with Koxinga's Ming loyalists in the Kingdom of Tungning (in Taiwan) until 1683. Zhu Shugui proclaimed that he acted in the name of the deceased Yongli Emperor. The Qing eventually sent the seventeen Ming princes still living in Taiwan back to mainland China where they spent the rest of their lives.

In 1725 the Qing Yongzheng Emperor bestowed the hereditary title of Marquis on a descendant of the Ming dynasty Imperial family, Zhu Zhilian (朱之璉), who received a salary from the Qing government and whose duty was to perform rituals at the Ming tombs. The Chinese Plain White Banner was also inducted in the Eight Banners. Later the Qianlong Emperor bestowed the title Marquis of Extended Grace posthumously on Zhu Zhilian in 1750, and the title passed on through twelve generations of Ming descendants until the end of the Qing dynasty in 1912. The last Marquis of Extended Grance was Zhu Yuxun (朱煜勳). In 1912, after the overthrow of the Qing dynasty in the Xinhai Revolution, some advocated that a Han Chinese be installed as Emperor, either the descendant of Confucius, who was the Duke Yansheng, or the Ming dynasty Imperial family descendant, the Marquis of Extended Grace.

When the Ming founder Hongwu came upon the mechanical devices housed in the Yuan dynasty's palace at Khanbaliq – such as fountains with balls dancing on their jets, self-operating tiger automata, dragon-headed devices that spouted mists of perfume, and mechanical clocks in the tradition of Yi Xing (683–727) and Su Song (1020–101) – he associated all of them with the decadence of Mongol rule and had them destroyed. This was described in full length by the Divisional Director of the Ministry of Works, Xiao Xun, who also carefully preserved details on the architecture and layout of the Yuan dynasty palace. Later, European Jesuits such as Matteo Ricci and Nicolas Trigault would briefly mention indigenous Chinese clockworks that featured drive wheels. However, both Ricci and Trigault were quick to point out that 16th-century European clockworks were far more advanced than the Common time keeping devices in China, which they listed as water clocks, incense clocks, and "other instruments ... with wheels rotated by sand as if by water" (Chinese: 沙漏). Chinese records – namely the Yuan Shi – describe the 'five-wheeled sand clock', a mechanism pioneered by Zhan Xiyuan (fl. 1360–80) which featured the scoop wheel of Su Song's earlier astronomical clock and a stationary dial face over which a pointer circulated, similar to European Models of the time. This sand-driven wheel clock was improved upon by Zhou Shuxue (fl. 1530–58) who added a fourth large gear wheel, changed gear ratios, and widened the orifice for collecting sand grains since he criticized the earlier model for clogging up too often.

While the Yongle Emperor had staged five major offensives north of the Great Wall against the Mongols and the Oirats, the constant threat of Oirat incursions prompted the Ming authorities to fortify the Great Wall from the late 15th century to the 16th century; nevertheless, John Fairbank notes that "it proved to be a futile military gesture but vividly expressed China's siege mentality." Yet the Great Wall was not meant to be a purely defensive fortification; its towers functioned rather as a series of lit beacons and signalling stations to allow rapid warning to friendly units of advancing enemy troops.

The period was also renowned for ceramics and porcelains.The major production centers for porcelain were the imperial kilns at Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province and Dehua in Fujian province. The Dehua porcelain factories catered to European tastes by creating Chinese export porcelain by the 16th century. Individual potters also became known, such as He Chaozong, who became famous in the early 17th century for his style of white porcelain sculpture. In The Ceramic Trade in Asia, Chuimei Ho estimates that about 16% of late Ming era Chinese ceramic exports were sent to Europe, while the rest were destined for Japan and South East Asia.