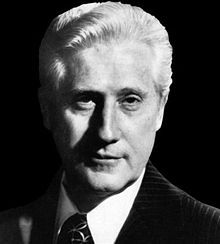

Jack Limpert published evidence as early as 1974 that Felt was the informant. On June 25 of that year, a few weeks after All the President's Men was published, The Wall Street Journal ran an editorial, "If You Drink Scotch, Smoke, Read, Maybe You're Deep Throat." It began "W. Mark Felt says he isn't now, nor has he ever been Deep Throat." The Journal quoted Felt saying the character was a "composite" and "I'm just not that kind of person." In 1975, George V. Higgins wrote: "Mark Felt knows more reporters than most reporters do, and there are some who think he had a Washington Post alias borrowed from a dirty movie." During a grand jury investigation in 1976, Felt was called to testify. The prosecutor, J. Stanley Pottinger, Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights, discovered that Felt was "Deep Throat", but the secrecy of the proceedings protected the information from being public.