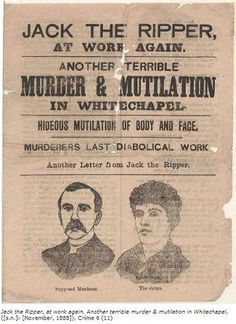

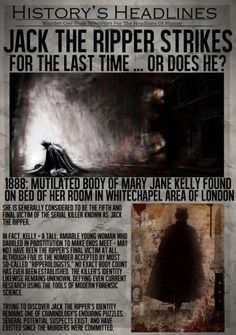

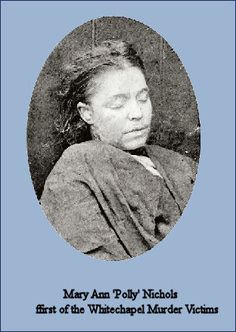

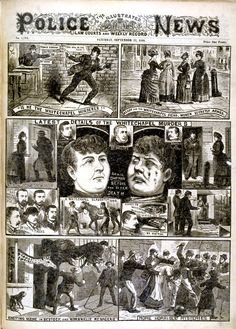

In the mid-19th century, Britain experienced an influx of Irish immigrants who swelled the populations of the major cities, including the East End of London. From 1882, Jewish refugees from pogroms in Tsarist Russia and other areas of Eastern Europe emigrated into the same area. The parish of Whitechapel in London's East End became increasingly overcrowded. Work and housing conditions worsened, and a significant economic underclass developed. Robbery, violence, and alcohol dependency were commonplace, and the endemic poverty drove many women to prostitution. In October 1888, London's Metropolitan Police Service estimated that there were 62 brothels and 1,200 women working as prostitutes in Whitechapel. The economic problems were accompanied by a steady rise in social tensions. Between 1886 and 1889, frequent demonstrations led to police intervention and public unrest, such as that of 13 November 1887. Anti-semitism, crime, nativism, racism, social disturbance, and severe deprivation influenced public perceptions that Whitechapel was a notorious den of immorality. In 1888, such perceptions were strengthened when a series of vicious and grotesque murders attributed to "Jack the Ripper" received unprecedented coverage in the media.