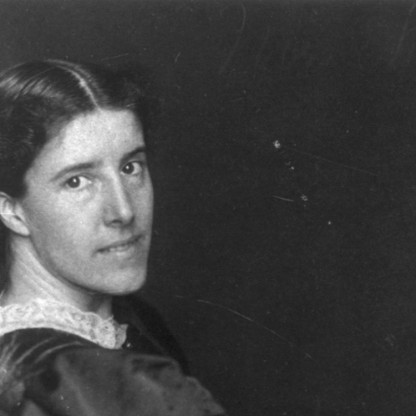

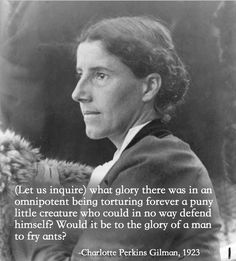

| Who is it? | Writer |

| Birth Day | July 03, 1860 |

| Birth Place | Hartford, Connecticut, United States |

| Charlotte Perkins Gilman age | 159 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | August 17, 1935(1935-08-17) (aged 75)\nPasadena, California, U.S. |

| Birth Sign | Leo |

| Occupation | Writer, commercial artist, magazine editor, lecturer and social reformer |

| Notable works | "The Yellow Wallpaper" Herland Women and Economics |

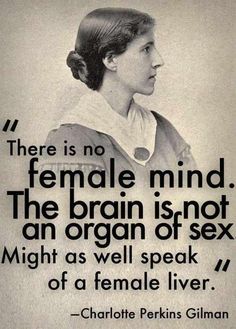

Charlotte Perkins Gilman was an accomplished American writer whose net worth is estimated to be $19 million in 2024. She gained recognition for her influential works on feminist literature and social reform. Gilman's most notable work, "The Yellow Wallpaper," highlighted the oppressive treatment of women in society. Beyond her valuable contributions to literature, Gilman was a prominent advocate for women's rights, lecturing extensively on gender equality and economic independence. Her impactful writings and dedicated activism have undoubtedly cemented her legacy as a pioneering figure in American literature and women's rights.

Gilman was born on July 3, 1860 in Hartford, Connecticut, to Mary Perkins (formerly Mary Fitch Westcott) and Frederic Beecher Perkins. She had only one brother, Thomas Adie, who was fourteen months older, because a physician advised Mary Perkins that she might die if she bore other children. During Charlotte's infancy, her father moved out and abandoned his wife and children, leaving them in an impoverished state. Since their mother was unable to support the family on her own, the Perkins were often in the presence of her father's aunts, namely Isabella Beecher Hooker, a suffragist, Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom's Cabin, and Catharine Beecher, educationalist.

Her natural intelligence and breadth of knowledge always impressed her teachers, who were nonetheless disappointed in her because she was a poor student. Her favorite subject was "natural philosophy," especially what later would become known as physics. In 1878, the eighteen-year-old enrolled in classes at the Rhode Island School of Design with the monetary help of her absent father, and subsequently supported herself as an Artist of trade cards. She was a tutor, and encouraged others to expand their artistic creativity. She was also a Painter.

Perkins-Gilman married Charles Stetson in 1884, and less than a year later gave birth to their daughter Katharine. Already susceptible to depression, her symptoms were exacerbated by marriage and motherhood. A good proportion of her diary entries from the time she gave birth to her daughter until several years later describe the oncoming depression that she was to face.

On April 18, 1887, Gilman wrote in her diary that she was very sick with "some brain disease" which brought suffering that cannot be felt by anybody else, to the point that her "mind has given way." To begin, the patient could not even leave her bed, read, write, sew, talk, or feed herself.

During the summer of 1888, Charlotte and Katharine spent time in Bristol, Rhode Island, away from Walter, and it was there where her depression began to lift. She writes of herself noticing positive changes in her attitude. She returned to Providence in September. She sold property that had been left to her in Connecticut, and went with a friend, Grace Channing, to Pasadena where the cure of her depression can be seen through the transformation of her intellectual life.

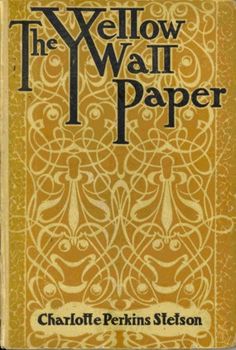

Although it was not the first or longest of her works, without question Gilman's most famous piece is her short story "The Yellow Wallpaper", which became a best-seller of the Feminist Press. She wrote it on June 6 and 7, 1890 in her home of Pasadena, and it was printed a year and a half later in the January 1892 issue of The New England Magazine. Since its original printing, it has been anthologized in numerous collections of women's literature, American literature, and textbooks, though not always in its original form. For instance, many textbooks omit the phrase "in marriage" from a very important line in the beginning of story: "John laughs at me, of course, but one expects that in marriage." The reason for this omission is a mystery, as Gilman's views on marriage are made clear throughout the story.

After her mother died in 1893, Gilman decided to move back east for the first time in eight years. She contacted Houghton Gilman, her first cousin, whom she had not seen in roughly fifteen years, who was a Wall Street attorney. They began spending a significant amount of time together almost immediately and became romantically involved. While she would go on lecture tours, Houghton and Charlotte would exchange letters and spend as much time as they could together before she left. In her diaries, she describes him as being "pleasurable" and it is clear that she was deeply interested in him. From their wedding in 1900 until 1922, they lived in New York City. Their marriage was nothing like her first one. In 1922, Gilman moved from New York to Houghton's old homestead in Norwich, Connecticut. Following Houghton's sudden death from a cerebral hemorrhage in 1934, Gilman moved back to Pasadena, California, where her daughter lived.

In 1894–95 Gilman served as Editor of the magazine The Impress, a literary weekly that was published by the Pacific Coast Women's Press Association (formerly the Bulletin). For the twenty weeks the magazine was printed, she was consumed in the satisfying accomplishment of contributing its poems, editorials, and other articles. The short-lived paper's printing came to an end as a result of a social bias against her lifestyle which included being an unconventional mother and a woman who had divorced a man. After a four-month-long lecture tour that ended in April 1897, Gilman began to think more deeply about sexual relationships and economics in American life, eventually completing the first draft of Women and Economics (1898). This book discussed the role of women in the home, arguing for changes in the practices of child-raising and housekeeping to alleviate pressures from women and potentially allow them to expand their work to the public sphere. The book was published in the following year, and propelled Gilman into the international spotlight. In 1903, she addressed the International Congress of Women in Berlin, and, the next year, toured in England, the Netherlands, Germany, Austria, and Hungary.

At one point, Gilman supported herself by selling soap door to door. After moving to Pasadena, Gilman became active in organizing social reform movements. As a delegate, she represented California in 1896 at both the National American Woman Suffrage Association convention in Washington, D.C. and the International Socialist and Labor Congress in London. In 1890, she was introduced to Nationalist Clubs movement which worked to "end capitalism's greed and distinctions between classes while promoting a peaceful, ethical, and truly progressive human race." Published in the Nationalist magazine, her poem, "Similar Cases" was a satirical review of people who resisted social change and she received positive feedback from critics for it. Throughout that same year, 1890, she became inspired enough to write fifteen essays, poems, a novella, and the short story The Yellow Wallpaper. Her career was launched when she began lecturing on Nationalism and gained the public's eye with her first volume of poetry, In This Our World, published in 1893. As a successful lecturer who relied on giving speeches as a source of income, her fame grew along with her social circle of similar-minded Activists and Writers of the feminist movement.

Although Gilman had gained international fame with the publication of Women and Economics in 1898, by the end of World War I, she seemed out of tune with her times. In her autobiography she admitted that "unfortunately my views on the sex question do not appeal to the Freudian complex of today, nor are people satisfied with a presentation of religion as a help in our tremendous work of improving this world."

Gilman also believed old stock Americans of British colonial descent were giving up their country to immigrants who, she said, were diluting the nation's reproductive purity. When asked about her stance on the matter during a trip to London she famously quipped "I am an Anglo-Saxon before everything." However, in an effort to gain votes for all women, she spoke out against the literacy requirements for the right to vote at the national American Women's Suffrage Association convention which took place in 1903 in New Orleans.

The Forerunner. Seven volumes, 1909–16. Microfiche. NY: Greenwood, 1968.

In January 1932, Gilman was diagnosed with incurable breast cancer. An advocate of euthanasia for the terminally ill, Gilman committed suicide on August 17, 1935 by taking an overdose of chloroform. In both her autobiography and suicide note, she wrote that she "chose chloroform over cancer" and she died quickly and quietly.

The story is about a woman who suffers from mental illness after three months of being closeted in a room by her husband for the sake of her health. She becomes obsessed with the room's revolting yellow wallpaper. Gilman wrote this story to change people's minds about the role of women in society, illustrating how women's lack of autonomy is detrimental to their mental, emotional, and even physical wellbeing. This story was inspired by her treatment from her first husband. The narrator in the story must do as her husband, who is also her Doctor, demands, although the treatment he prescribes contrasts directly with what she truly needs — mental stimulation and the freedom to escape the monotony of the room to which she is confined. "The Yellow Wallpaper" was essentially a response to the Doctor who had tried to cure her of her depression through a "rest cure", Dr. Silas Weir Mitchell, and she sent him a copy of the story.

With regard to African Americans, Gilman wrote in the American Journal of Sociology: "The Problem, is this: Given: in the same country, Race A, progressed in social evolution, say, to Status 10; and Race B, progressed in social evolution, say, to Status 4.. . . Given: that Race B, in its present condition, does not develop fast enough to suit Race A. Question: How can Race A best and most quickly promote the development of Race B?" Gilman’s solution was that all blacks beneath "a certain grade of citizenship" — those who were not "decent, self-supporting, [and] progressive" — "should be taken hold of by the state."