| Who is it? | Actor, Producer, Director |

| Birth Day | June 19, 2017 |

| Birth Place | Turkey, American |

| Age | 6 YEARS OLD |

| Birth Sign | Cancer |

| Court | U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania |

| Full case name | Blake J. Robbins, Michael E. Robbins and Holly S. Robbins, individually, and on behalf of all similarly situated persons v. Lower Merion School District, the Board of Directors of the Lower Merion School District, and Christopher W. McGinley, Superintendent of Lower Merion School District |

| Decided | Settled October 2010 ($610,000) |

| Citation(s) | No. 10-0665 |

| Related action(s) | Hasan v. Lower Merion School District (filed July 27, 2010) |

| Judge(s) sitting | Senior U.S. District Judge Jan E. DuBois |

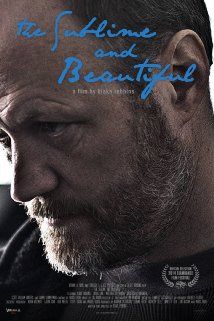

Blake Robbins' net worth is estimated to reach $100,000 in 2024. He is widely recognized as a highly versatile talent in the American entertainment industry, excelling in the roles of an actor, producer, and director. Robbins has showcased his immense skills and creativity across various projects, cementing his status as a prominent figure in the industry. With an impressive body of work under his belt, his net worth is a testament to his commitment and dedication to his craft. As he continues to make waves in the entertainment world, it is clear that Blake Robbins' influence and success will only continue to grow.

I would not find this a problem if students were informed that this was possible, for privacy's sake. However, what was appalling was that not only did the District not inform parents and students of this fact … [W]hile you may feel that you can say that this access will not be abused, I feel that this is not enough to ensure the integrity of students, and that even if it was no one would have any way of knowing (especially end-users). I feel it would be best that students and parents are informed of this before they receive their computers.... I could see not informing parents and students of this fact causing a huge uproar.

The lawsuit claimed that the district's use of the webcams violated the United States Constitution's guarantees of privacy of the students and their families and friends at home, as well as Pennsylvania Common law (expectation of privacy) and Section 1983 of the U.S. Civil Rights Act (right to privacy).

Dan Tynan, Executive Editor of PC World and author of Computer Privacy Annoyances (2005), said: "This is extremely creepy, and way beyond the purview of the school.... There's really no need to try to take a picture of someone—in fact, how can you prove the person in front of the laptop was the one who stole it?... And to install this stuff on anyone's computer and not notify them about, it is just begging for a world of pain." Robert Richardson, Director of the Computer Security Institute, said: "It's incredible that they didn't realize they were playing with fire." Technology Journalist Robert X. Cringely wrote in InfoWorld:

The school elected to enable TheftTrack to allow school district employees to secretly and remotely activate the standard webcam featured in all Apple laptops since 2006. That allowed school officials to secretly take photos through the webcam, of whatever was in front of it and in its line of sight, and send the photos to the school's server. The system snapped and sent a new photo every 15 minutes when the laptop was on, and TheftTrack was activated, though school employees could adjust the timeframe to as low as one-minute intervals. LANrev disabled the webcams for all other uses (e.g., students were unable to use Photo Booth or video chat), so most students mistakenly believed that their webcams did not work at all.

Investigators were not able to determine how often the images were viewed by school personnel. A total of 18 members of the district's systems staff had LANrev administrator permissions during the 2008–10 school years, and 16 of them had access to data stored on the LANrev server. Furthermore, those with access to the photos and screenshots could, and in some circumstances did, forward the photos and screenshots to others.

The district was put on notice of a third parallel suit that a third student intended to bring against the district, for "improper surveillance of the Lower Merion High School student on his school issued laptop", which included taking 729 webcam shots and screenshots between December 14, 2009, and February 18, 2010. The third student also learned about the school's surveillance of him when he received a letter from the district that the judge had ordered the district send to all students who had been subjected to webcam surveillance. Sources told Main Line Media News that the student never reported the computer missing.

In October 2010, the school district agreed to pay $610,000 to settle the Robbins and Hasan lawsuits against it. The settlement must be approved by Judge DuBois, who could also make his injunction barring the district from secretly tracking students permanent. The settlement also includes $175,000 that will be placed in a trust for Robbins and $10,000 for Hasan. The attorneys for Robbins and Hasan get $425,000.

The litigation also prompted new legislation in New Jersey, sponsored by New Jersey State Senator Donald Norcross. "Big Brother has no place in our schools. It's the administration's job to educate, not monitor their students," said Norcross. New Jersey's "Anti-Big Brother Act" (S-2057) was signed into law by New Jersey Governor Chris Christie on April 15, 2013. The law requires New Jersey school districts to notify students (and their parents) who receive electronic devices from their school that their activities may be monitored or recorded. It subjects a school district that fails to comply with the law's requirements to a fine of $250 per student, per incident.

The report also found that district officials knew that Robbins had taken his laptop home, but still decided to activate the covert surveillance that secretly captured hundreds of webcam photos and screenshots—included pictures of Robbins sleeping and partially undressed, a photo of his father, and images of instant messages and photos of friends with whom Robbins was video-chatting. After the program was activated on Robbins' computer, one district employee had emailed another: "Now currently online at home".