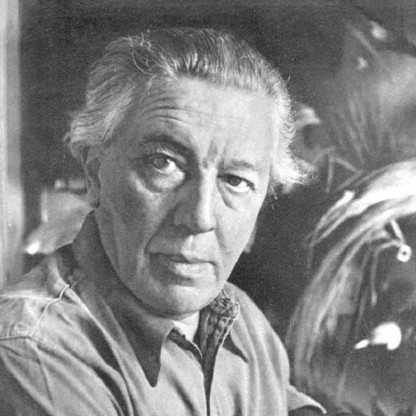

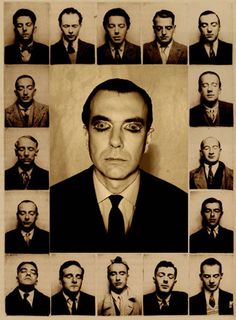

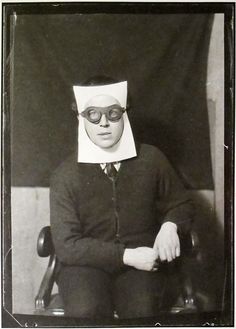

| Who is it? | Founder of Surrealism |

| Birth Day | February 18, 1896 |

| Birth Place | Tinchebray, Orne, France, French |

| Andre Breton age | 123 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 28 September 1966(1966-09-28) (aged 70)\nParis, France |

| Birth Sign | Pisces |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Period | 20th century |

| Genre | Histories, poetry, essays |

| Literary movement | Surrealism |

| Notable works | Surrealist Manifesto |

| Spouse | Simone Kahn (m. 1921; div. 1931) Jacqueline Lamba (m. 1934; div. 1943) Elisa Breton (m. 1945; his death 1966) |

| Children | Aube Breton |

Andre Breton's net worth is estimated to reach $14 million in 2024. Breton, a renowned figure in the world of art, is primarily recognized as the founder of Surrealism in the French artistic movement. His contributions to Surrealism and his influence on the art world have made him an icon in the field. With his innovative ideas and unique artistic vision, Breton has left a lasting impact on the art community, securing his place as one of the most influential figures in Surrealism.

In 1919 Breton launched the review Littérature with Louis Aragon and Philippe Soupault. He also associated with Dadaist Tristan Tzara. In 1924 he was instrumental in the founding of the Bureau of Surrealist Research.

Breton married his first wife, Simone Kahn, on 15 September 1921. The couple relocated to rue Fontaine # 42 in Paris on 1 January 1922. The apartment on rue Fontaine (in the Pigalle district) became home to Breton's collection of more than 5,300 items: modern paintings, drawings, sculptures, photographs, books, art catalogs, journals, manuscripts, and works of popular and Oceanic art. He was an atheist.

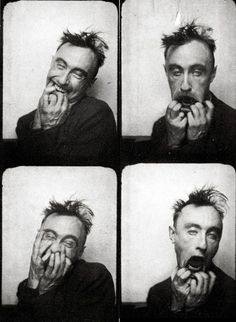

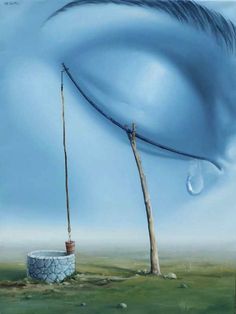

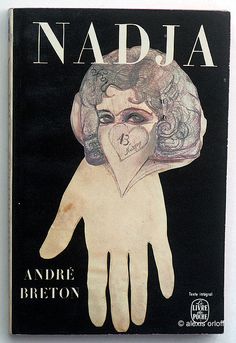

In a publication The Magnetic Fields (Les Champs Magnétiques), a collaboration with Soupault, he implemented the principle of automatic writing. He published the Surrealist Manifesto in 1924, and was Editor of the magazine La Révolution surréaliste from 1924. A group of Writers became associated with him: Philippe Soupault, Louis Aragon, Paul Éluard, René Crevel, Michel Leiris, Benjamin Péret, Antonin Artaud, and Robert Desnos.

Anxious to combine the themes of personal transformation found in the works of Arthur Rimbaud with the politics of Karl Marx, Breton joined the French Communist Party in 1927, from which he was expelled in 1933. During this time, he survived mostly by the sale of paintings from his art gallery.

Breton was an avid collector of art, ethnographic material, and unusual trinkets. He was particularly interested in materials from the North West coast of North America. During a financial crisis he experienced in 1931, most of his collection (along with his friend Paul Éluard's) was auctioned. He subsequently rebuilt the collection in his studio and home at 42 rue Fontaine. The collection grew to over 5,300 items: modern paintings, drawings, sculptures, photographs, books, art catalogs, journals, manuscripts, and works of popular and Oceanic art.

In 1935, there was a conflict between Breton and the Soviet Writer and Journalist Ilya Ehrenburg during the first "International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture" which opened in Paris in June. Breton had been insulted by Ehrenburg—along with all fellow surrealists—in a pamphlet which said, among other things, that surrealists were "pederasts". Breton slapped Ehrenburg several times on the street, which resulted in surrealists being expelled from the Congress. Crevel, who according to Salvador Dalí, was "the only serious communist among surrealists" was isolated from Breton and other surrealists, who were unhappy with Crevel because of his homosexuality and annoyed with communists in general.

In 1938, Breton accepted a cultural commission from the French government to travel to Mexico. After a conference at the National Autonomous University of Mexico about surrealism, Breton stated after getting lost in Mexico City (as no one was waiting for him at the airport) "I don't know why I came here. Mexico is the most surrealist country in the world".

In 1941, Breton left France due to World War II. He emigrated to New York City and lived there for a few years. In 1942, Breton organized a groundbreaking Surrealist exhibition at Yale University. Breton returned to Paris in 1946, where he opposed French colonialism (for Example as a signatory of the Manifesto of the 121 against the Algerian war) and continued, until his death, to foster a second group of surrealists in the form of expositions or reviews (La Brèche, 1961–65). In 1959, he organized an exhibit in Paris.

In 1942, Breton collaborated with Artist Wifredo Lam on the publication of Breton's poem "Fata Morgana", which was illustrated by Lam.

In 1944, he and Elisa traveled to the Gaspé Peninsula in Québec, where he wrote Arcane 17, a book which expresses his fears of World War II, describes the marvels of the Rocher Percé and the extreme northeastern part of North America, and celebrates his new romance with Elisa.

By the end of World War II André Breton decided to embrace anarchism explicitly. In 1952 Breton wrote "It was in the black mirror of anarchism that surrealism first recognised itself." Breton was consistent in his support for the francophone Anarchist Federation and he continued to offer his solidarity after the Platformists around Fontenis transformed the FA into the Fédération Communiste Libertaire.

After Breton's death on 28 September 1966, Breton's third wife, Elisa, and his daughter, Aube, allowed students and researchers access to Breton's archive and collection. After thirty-six years, when attempts to establish a surrealist foundation to protect the collection were opposed, the collection was auctioned by Calmels Cohen at Drouot-Richelieu. A wall of the apartment is preserved at the Centre Georges Pompidou.

French Anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, in an interview in 1971, spoke about Breton's skill in determining the authenticity of objects. Strauss even described their friendship while the two were living in New York: "We lived in New York between 1941 and 1945 in a great friendship, running museums and antiquarians together. I owe him a lot about the knowledge and appreciation of objects. I've never seen him [Breton] doing a mistake on exotic and unusual objects. When I say a mistake, I mean about its authenticity but also its quality. He [Breton] had a sense, almost of divination."

Nine previously unpublished manuscripts, including the Manifeste du surréalisme, were auctioned by Sotheby's in May 2008.

During André Breton’s visit to Haiti in 1945-46, the French surrealist leader sought to connect surrealist politics and automatist practices with the legacies of the Haitian Revolution and the ritual practices of Vodou possession. Recent developments in Haitian painting were central to his efforts, as can be seen from a comment that Breton left in the visitors’ book at the Centre d’Art in Port-au-Prince: “Haitian painting will drink the blood of the phoenix. And, with the epaulets of [Jean-Jacques] Dessalines, it will ventilate the world.” Breton was specifically referring to the work of Painter and Vodou priest Hector Hyppolite, whom he identified as the first Artist to directly depict Vodou scenes and the lwa (Vodou deities), as opposed to hiding them in chromolithographs of Catholic saints or invoking them through impermanent vevé (abstracted forms drawn with powder during rituals). Breton’s writings on Hyppolite were undeniably central to the artist’s international status from the late 1940s on, but the surrealist readily admitted that his understanding of Hyppolite's art was inhibited by their lack of a Common language. Returning to France with multiple paintings by Hyppolite, Breton integrated this artwork into the increased surrealist focus on the occult, myth and magic.