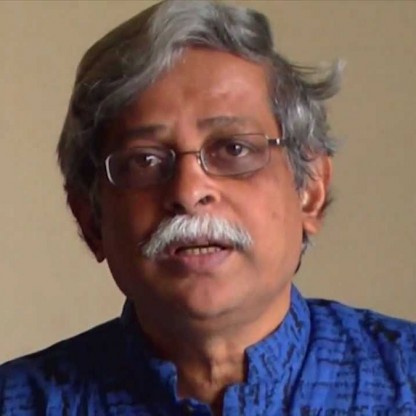

| Who is it? | Science Fiction Author |

| Birth Day | April 26, 1912 |

| Birth Place | Manitoba, Canada, Canadian |

| A. E. van Vogt age | 108 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | January 26, 2000(2000-01-26) (aged 87)\nLos Angeles, California, US |

| Birth Sign | Taurus |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Period | 1939–1986 (science fiction) |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Literary movement | Golden Age of Science Fiction |

| Spouse | Edna Mayne Hull (1939–1975) Lydia van Vogt (until his death) |

A. E. van Vogt, the renowned Canadian science fiction author, is anticipated to have a net worth of $8 million by 2024. His extraordinary contribution to the genre has solidified his position as one of the most influential figures in science fiction literature. Van Vogt's captivating storytelling abilities and imaginative narratives have captivated readers for generations, making him an integral part of the genre's history. His vast wealth can be attributed to the success of his numerous celebrated works, which have garnered both critical acclaim and a dedicated fanbase worldwide. A. E. van Vogt's legacy as a science fiction author remains unmatched, and his estimated net worth serves as a testament to his unparalleled impact on the genre.

Childhood was a terrible period for me. I was like a ship without anchor being swept along through darkness in a storm. Again and again I sought shelter, only to be forced out of it by something new.

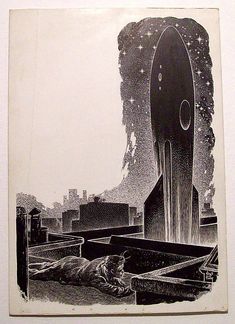

Van Vogt began his writing career with stories in the true confession style of pulp magazines such as True Story. He decided to switch to writing science fiction, which he enjoyed. He was inspired by the August 1938 issue of Astounding Science Fiction, which he picked up at a newsstand. John W. Campbell's novelette "Who Goes There?" (later adapted into The Thing from Another World and The Thing) inspired van Vogt to write "Vault of the Beast", which he submitted to that same magazine. Campbell, who edited Astounding (and had written the story under a pseudonym), sent van Vogt a rejection letter, but one which encouraged van Vogt to try again. Van Vogt sent another story, entitled "Black Destroyer," which was accepted. A revised version of "Vault of the Beast" would be published in 1940.

Van Vogt's first SF publication was inspired by The Voyage of the Beagle by Charles Darwin. "The Black Destroyer" was published in July 1939 by John W. Campbell in Astounding Science Fiction, the centennial year of Darwin's journal. It featured a fierce, carnivorous alien, the coeurl, stalking the crew of an exploration spaceship. "Discord in Scarlet" was his second story to be published, also appearing as the cover story. It was accompanied by interior illustrations created by Frank Kramer and Paul Orban. (Van Vogt and Kramer thus debuted in the issue of Astounding that is sometimes identified as the start of the Golden Age of Science Fiction.) The former story served as the inspiration for multiple science fiction movies. In 1950, the two were combined with two other stories as a fix-up novel, The Voyage of the Space Beagle (Simon & Schuster), which was published in at least five European languages by 1955. Positing the need for exobiologists who will appreciate the differences between the inhabitants of other planets and ourselves, it stresses the importance of the civilian rather than military in exploration of other cultures.

He subsequently wrote three novels merging these overarching themes, The World of Null-A and The Pawns of Null-A in the late 1940s, and Null-A Three in the early 1980s. Null-A, or non-Aristotelian logic, refers to the capacity for, and practice of, using intuitive, inductive reasoning (compare fuzzy logic), rather than reflexive, or conditioned, deductive reasoning.

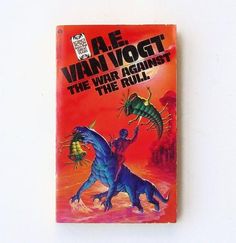

Others saw van Vogt's talent and stardom from his first story, and in 1941, van Vogt decided to become a full-time Writer, quitting his job at the Canadian Department of National Defence. Prolific for a few years, van Vogt wrote many short stories. In the 1950s, many of them were retrospectively patched together into novels, or "fixups" as he called them, a term that entered the vocabulary of science-fiction criticism. When the original stories were related (e.g., The War against the Rull) this was often successful. When not (e.g., Quest for the Future) the disparate stories thrown together generally made for a less coherent plot.

In 1944, van Vogt moved to Hollywood, where his writing took on new dimensions after World War II. He was always interested in the idea of all-encompassing systems of knowledge (akin to modern meta-systems)—the characters in his very first story used a system called "Nexialism" to analyze the alien's behavior, and he became interested in the general semantics of Alfred Korzybski.

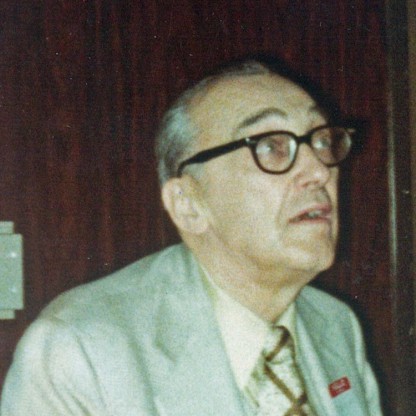

Critical opinion about the quality of van Vogt's work is sharply divided. An early and articulate critic was Damon Knight. In a 1945 chapter-long essay reprinted in In Search of Wonder, entitled "Cosmic Jerrybuilder: A. E. van Vogt", Knight described van Vogt as "no giant; he is a pygmy who has learned to operate an overgrown typewriter". Knight described The World of Null-A as "one of the worst allegedly adult science fiction stories ever published". Concerning van Vogt's writing, Knight said:

In 1946, van Vogt and his first wife, Edna Mayne Hull, were Guests of Honor at the fourth World Science Fiction Convention.

It is generally held that the "damnable SFWA politics" concerns Damon Knight, the founder of the SFWA, who abhorred van Vogt's style and politics and thoroughly demolished his literary reputation in the 1950s.

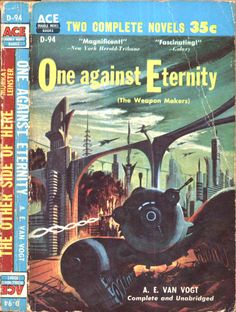

In 1951, he published The Weapon Shops of Isher. In the same decade, van Vogt also produced collections and fixups such as The Mixed Men (1952), The War Against the Rull (1959), and the two "Clane" novels, Empire of the Atom (1957) and The Wizard of Linn (1962), which were inspired (like Asimov's Foundation series) by Roman imperial history, specifically the reign of Claudius. His later novels included fixups such as The Beast (also known as Moonbeast) (1963), Rogue Ship (1965), Quest for the Future (1970) and Supermind (1977); expanded short stories such as The Darkness on Diamondia (1972) and Future Glitter (also known as Tyranopolis; 1973); original novels such as Children of Tomorrow (1970), The Battle of Forever (1971) and The Anarchistic Colossus (1977); plus sequels to his classic works, many of which were promised, but only one of which appeared, Null-A Three (1984; originally published in French). Several later books were original in Europe, and at least one novel only ever appeared in Italian.

The works of van Vogt were translated into French by the surrealist Boris Vian (The World of Null-A as Le Monde des Å in 1958), and van Vogt's works were "viewed as great literature of the surrealist school". In addition, Slan was published in French, translated by Jean Rosenthal, under the title À la poursuite des Slans, as part of the paperback series 'Editions J'ai Lu: Romans-Texte Integral' in 1973, this edition also listing the following works by van Vogt as having been published in French as part of this series: Le Monde des Å, La faune de l'espace, Les joueurs du Å, L'empire de l'atome, Le sorcier de Linn, Les armureries d'Isher, Les fabricants d'armes, and Le livre de Ptath.

Van Vogt was profoundly affected by revelations of totalitarian police states that emerged after World War II. He wrote a mainstream novel that he set in Communist China, The Violent Man (1962); he said that to research this book he had read 100 books about China. Into this book he incorporated his view of "the violent male type", which he described as a "man who had to be right", a man who "instantly attracts women" and who he said were the men who "run the world".

Knight also expressed misgivings about van Vogt's politics. He noted that van Vogt's stories almost invariably present absolute monarchy in a favorable light. In 1974, Knight retraced some of his criticism after finding out about Vogt's working methods about writing down his dreams:

In 1980, van Vogt received a "Casper Award" (precursor to the Canadian Prix Aurora Awards) for Lifetime Achievement.

The Science Fiction Writers of America named him its 14th Grand Master in 1995 (presented 1996). Great controversy within SFWA accompanied its long wait in bestowing its highest honor (limited to living Writers, no more than one annually). Writing an obituary of van Vogt, Robert J. Sawyer, a fellow Canadian Writer of science fiction remarked:

In 1996, van Vogt received a Special Award from the World Science Fiction Convention "for six decades of golden age science fiction". That same year, the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame inducted him in its inaugural class of two deceased and two living persons, along with Writer Jack Williamson (also living) and editors Hugo Gernsback and John W. Campbell.

Harlan Ellison was more explicit in 1999 introduction to Futures Past: The Best Short Fiction of A. E. van Vogt:

On January 26, 2000, van Vogt died in Los Angeles, United States from Alzheimer's disease, survived by his second wife, the former Lydia Bereginsky.

In The John W. Campbell Letters, Campbell says, "The son-of-a-gun gets hold of you in the first paragraph, ties a knot around you, and keeps it tied in every paragraph thereafter—including the ultimate last one".

Dick also defended van Vogt against Damon Knight’s criticisms: